Fran Cusworth meets families who have loved – and lost – their babies before they had a chance to get to know them

They’re little people, sometimes small enough to fit on a father’s hand. But these are not little deaths. The grief that surrounds the death of a baby in pregnancy, birth or in the fragile early days of life can be seismic. It can break up marriages, shape a family’s dynamics forever and it lasts a lifetime.

Renee Fallon spent four years doing IVF before she became pregnant with Bethany. But 19 weeks into the pregnancy, after a wisdom tooth infection, Renee’s membranes ruptured and contractions began. Bethany was born alive, but survived for little more than an hour.

Renee and her husband Paul held a funeral, inviting around 40 people, and then a party a year later, with a jumping castle, to remember Bethany.

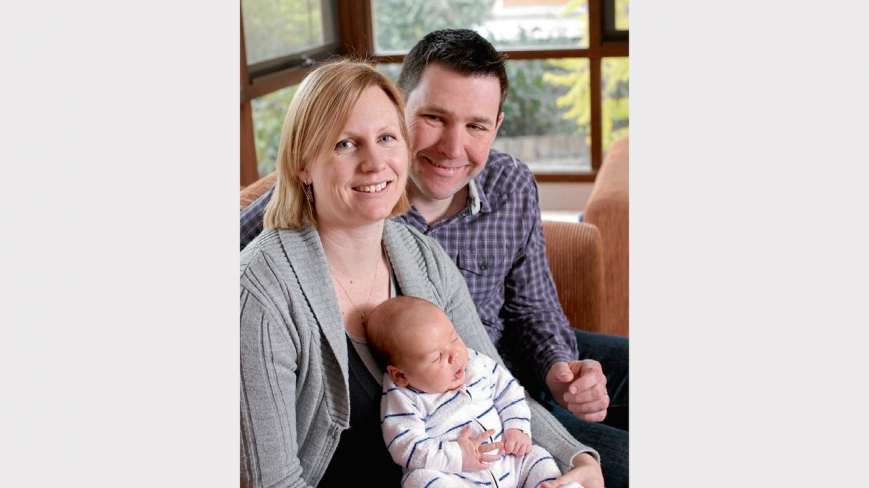

Three years on, now with a healthy two-year-old daughter and a two-month-old son, they still mark Bethany’s birthday with a cake, and Renee is the Victorian organiser of Pregnancy Loss Australia.

While they’ve been surrounded by supportive friends and family, the Fallons say there are those who don’t understand the grief for a baby born early, who seem embarrassed by it.

‘‘We had a few friends who declined to come to the funeral. They said it just wasn’t their thing,’’ Paul says. ‘‘You drift away from those people.’’

On Sunday, September 16, Pregnancy Loss Australia will hold its annual memorial walkathon in Doncaster, releasing balloons to represent the lives cut short.

Once, such things weren’t talked about at all. Stillborn babies were whisked away from mothers before they could even hold them and buried in a communal grave. Out of sight, out of mind, it was believed. But older women say they never forget the loss, or the way they were treated during this era.

‘‘I never got to hold the baby,’’ says 66-year-old Lynne Vago, from North Melbourne, whose full-term baby, Alina-Jane, died at just 30 hours from a heart defect present at birth. ‘‘I was sent home with a sleeping tablet and a prescription to dry up the milk.

‘‘Back when it happened, it was very bad form to talk about it. You kept a stiff upper lip, or you might make somebody feel bad.

‘‘I got home and thought, ‘How could we have left the hospital without the baby, without telling her we loved her?’ ’’

But times have changed. Many parents have funerals for babies who have died in utero or from early delivery, and most parents get the chance to hold the body of their son or daughter.

When you expected to spend years raising a child, but you only have a few hours with them, how do you spend that precious time? People name their babies. They take photographs and handprints. They gently wash and dress them. And above all, they hold them.

Heartfelt is a not-for-profit organisation that uses professional photographers, who volunteer to come at short notice to take pictures of stillborn or critically ill babies and children, for free.

The organisation’s national president Gavin Blue says professionals can carefully frame and light a photograph to reduce the disturbing impact of the medical aspects.

‘‘Talking about stillborn children is still a social taboo, and people do shy away, so it really helps if people have a photograph they feel comfortable sharing, that won’t upset people.’’

While women’s grief can be further complicated by the physical impact of childbirth – sometimes labouring to give birth to a baby they know has died – men’s anxiety for their wives and partners can mean they fail to acknowledge their own sadness.

Psychologist Penny Brabin, a specialist in grief counselling for baby loss, and on the board of the International Stillbirth Alliance, says grief-stricken fathers can be neglected in the focus on mothers. ‘‘But men have been in labour wards since the late ’70s, so these days they are much more part of it.’’

With ultrasound images of babies in utero available so early now, parents attach much earlier to the idea of their baby, she says. ‘‘We have fewer babies, and we have more control over pregnancy, and women are more vocal – all these things have changed the way we respond to the loss of a baby.’’

Hospital staff are these days much more aware of how to deal with parents who have lost a baby, she says. ‘‘Most of these parents are relatively young and some haven’t seen death before.’’

While much has changed for the better in the past few decades, she says more attention is needed to help parents handle the terror of subsequent pregnancies after losing a baby. ‘‘A lot of women are really suffering through it. We need some better programs in place.’’

Diamond Creek mother Amber Bull’s first child was stillborn at 24 weeks. While she now has two healthy children, she says her later pregnancies were periods of high anxiety.

‘‘With the next pregnancy, I couldn’t enjoy it. I felt angry about that, like I’d lost my innocence,’’ she says. ‘‘With the second one it was even worse. I felt like, ‘When’s my luck going to run out?’ ’’

Surrounded at home by pictures of babies, children and family, sipping tea while her newborn son naps, she says the loss has changed her profoundly. ‘‘I make a concerted effort to appreciate every day, and to remember how lucky we are to have two healthy children,’’ she says.

‘‘The things we once might have worried about, they’re insignificant now.’’

On Labour Day weekend this year, Kathryn Lieschke and her husband Lance were taking it easy at their South Morang home, their first child due in less than four weeks.

But on Sunday, March 11, it occurred to Kathryn she hadn’t felt her baby move for a day or so. She and Lance headed to hospital, expecting to be reassured with a scan, or at worst, taken for an emergency caesarean.

‘‘Even I could tell, looking at the scan, that there was no heartbeat,’’ says Lieschke, 29. The baby had died, the cause unknown.

After an induced 12-hour labour, the pair had 12 hours with their baby boy Toby, bathing, dressing and photographing him, and finally, saying goodbye.

‘‘I felt like my life couldn’t go on,’’ Kathryn says. ‘‘I felt I would never laugh, or ever be happy again.’’

They had a funeral 10 days later, then Kathryn returned to her job as a public servant much sooner than expected.

Six months on, she says the hardest thing to come to terms with is that life is moving on without the baby for whom she expected to be caring. ‘‘Even the seasons are changing. And Toby’s not here.’’

While she’s had strong support from close family and friends, she’s been a little shocked by acquaintances who seem surprised she didn’t get over it after a month or two, and by those who try to comfort her by saying she will have other children.

‘‘They think because we never met him, that it’s not like really losing him. But for us he was our child, our first-born child.

‘‘For us, Toby was very real. We felt him move and saw his heart beat. We made plans that included him. He was already part of our lives. Yes, we might have other babies. But they won’t replace Toby.’’

Four years after her baby boy died in utero at 24 weeks, Amber Bull’s voice still shakes when she talks about it.

These days she has a healthy two-year-old, and a six-week-old baby boy, but the loss of her first-born is still raw, she says.

She went to the Mercy Hospital with husband Travis for a scheduled check-up when she was 24 weeks’ pregnant, and was told there was no heartbeat.

‘‘I honestly can’t remember much. In some ways I think I’ve blocked it out. I think I went into shock. All I could think of was that I still had to give birth,’’ she says. ‘‘I was just numb, thinking ‘How am I going to get through this?’ ’’

After a 12-hour labour, the baby was born. ‘‘I think that was when it hit me, when I saw Travis holding him. I couldn’t even speak to him. I was just too upset. I was crying.’’

She went home, keen to ‘‘get out of there as fast as I could’’. Back home in Diamond Creek, she crawled into bed and stayed there for days.

Four days later they had a private ceremony at a funeral home. ‘‘That’s when we had a chance to say goodbye, to tell him that we loved him. It was just us. No celebrant.’’

Now 34, Bull says if she could do anything differently, she would have had photos taken. ‘‘I didn’t even realise it was something you could do. I really wish we had it now. You have so little to show for the whole experience … And I regret not having a funeral where we invited other members of the family because it would have helped them. But at the time, you just do what you have to do.’’

It was her first experience with death, and it has given her more empathy, she says.

‘‘It makes you stronger, in some ways. I feel like, if I can get through that I can get through anything. It’s made us stronger as a couple, for the same reason.’’

■ Pregnancy Loss Australia’s annual memorial walkathon is on Sunday, September 16 at Ruffey Lake Park, Doncaster. Register at 10am, start 11.30am. Details: visit pregnancylossaustralia.org.au.