What drives high achievers to return to a career after they’ve walked away? Linley Wilkie investigates.

FOR decades, Australians have proclaimed a patriotic love of football, meat pies, kangaroos and Holden cars. Surely it’s time “making a comeback” was added to the list. It’s hardly a new phenomenon – ‘‘more comebacks than Nellie Melba’’ has been part of our vernacular since her multiple “final performances” in the 1920s.

But the past few years have produced a spate of high-profile career resurrections.

Take the Olympic swimming trials in March, watched with intense interest as Michael Klim, Ian Thorpe, Geoff Huegill and Libby Trickett all came out of retirement in the quest for a ticket to London. Only Trickett made it.

On the entertainment front, John Farnham is the country’s most famous comeback king. After the rousing reception he received during his performance at Black Saturday’s Sound Relief concert in 2009, he was reportedly “tired of being retired” and announced his John Farnham Live by Demand national tour (his The Last Time tour was in 2002).

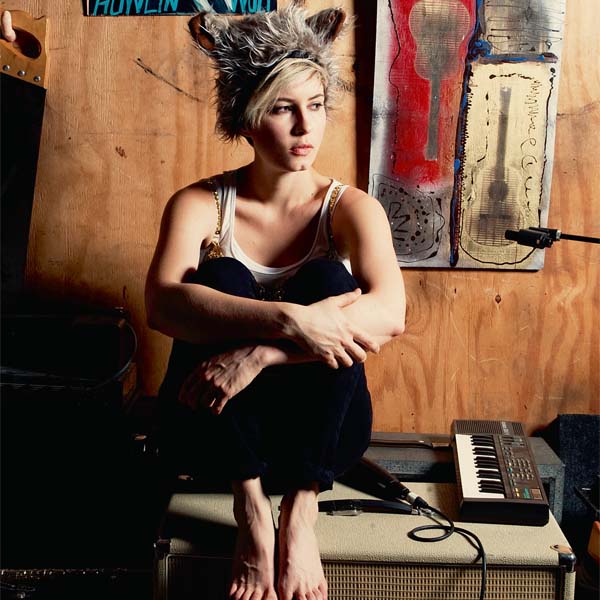

Now singer-songwriter Missy Higgins has returned to the spotlight with her third album, The Ol’ Razzle Dazzle, and accompanying tour after quietly quitting the music business in 2009.

But making a comeback isn’t the preserve of the rich and famous. While there are many reasons for walking away, the rationale for returning is often the same.

Higgins quit music in her mid-20s after a debilitating case of writer’s block. “I struggled with my inability to tap into the well of creativity,” says the multiple ARIA and APRA award winner. “I knew [what] I had inside me, I still really loved music, but I just couldn’t access it and really didn’t know how I was ever going to be able to express myself in that way again.”

For Higgins, retirement meant replacing the recording studio with a lecture theatre, enrolling in indigenous studies at Melbourne University. “I was informing myself on the issues and teaching myself the history of the country,” she says. During breaks from study, she would tinker on her piano in a rented Northcote apartment, take bike rides or long walks along Merri Creek and visit long-neglected friends whose birthdays and weddings she’d missed while she was touring around the world. She admits that at that stage she had no clue what life post-university would involve.

When Michael Klim retired in 2007, he’d already mapped out his next chapter. The Olympic gold medallist had been struggling with injuries and rehab since 2001 and, having lost passion for the sport, he called it quits. “It’s quite a big step for any athlete, because in most cases it’s our identity,” Klim says. “I was lucky that I’d set up a little bit of a life outside of swimming.”

Klim recognised commercial opportunities in the grooming industry and, in 2008, he launched Milk, a men’s skincare range. Then in 2010, partially motivated by the approaching London Olympics, he wondered if he was still capable of competing with the world’s best.

“I was still swimming reasonable times, so I thought ‘Why not give it a try?’” he says. “My kids [he and wife Lindy have three children] never saw me swim at a national level, so that was also a big motivation.”

He decided to train for six months and see what ensued. Satisfied with his progress, he continued for another year and made it to the Olympic trials. But when he came 14th in the 100 metres butterfly semi-final, he promptly announced his retirement, saying “That was my swan song.”

Refecting on his comeback attempt now, Klim says: “If I succeeded or not, my life really wasn’t going to change. I had a beautiful family waiting for me and a full-time job. So from that point of view, I wasn’t stressed either way. At least this time I retired on my own terms.”

Fellow Olympians Ian Thorpe and Geoff Huegill had different reasons for returning to competitive swimming. “Geoff had been pretty bad mentally [Huegill has talked publicly about issues with obesity and alcohol] and needed to go back to something that he knew, to get him out of the rut,” says Klim. “It saved his life and, through sport, he was able to get back to being happy. It’s probably the same for Ian, from a mental point of view. It comes back to that identity we grew up with. He’s more comfortable doing that than anything else.”

Missy Higgins can relate. “Part of the reason I kept on trying to write the album was because I didn’t know what else I would do,” she says. After a humbling performance at the all-female Lilith Fair music festival in America, where young fans flocked around her after the gig full of praise and curiosity about the next album, she realised her supporters still loved what she did.

“Ultimately I came back for myself, but the fans were a huge motivation in my self-confidence,” she says. “I realised that doing music is where my place is in the world. It was like an old friend who had gone missing and come back.”

In 2010, award-winning couturier Helen Manuell closed her designer frock business after struggling to compete financially with Chinese imports and online wedding dresses. “I guess because of things like the GST, people had to cut back and beautiful couture silk wedding dresses were the first thing to go,” she says.

“I was really angry and disappointed in what had become of an industry that used to be so revered.”

Manuell decided to renew the lease on her Armadale shopfront and convert it into a cafe, which she called Mr McQueen. She began serving lattes in August, but hated it by November. “God knows what I was thinking. Nothing like a dose of postnatal depression,” jokes the mother of two. “I was still getting phone calls from girls wanting me to make their wedding dresses and thought, ‘I think I’ve made the wrong decision’.”

Manuell sold the cafe early last year and returned to dressmaking, this time from her Glen Huntly home. She has orders that will keep her busy until mid-2014. “I’m doing it a lot smarter,” she says. “The prices I’m charging are a lot cheaper because I don’t have the overheads.”

Since returning to fashion, Manuell realises she was born to do it. “I’ve been sewing since I was not even five years old,” she says. “I went to uni and studied business, but I bloody hate accounting. Sure, I could do it if I needed to, but I pinch myself every day that my clients pay me to do what I love.”

Similarly, Klim says he was built to swim. “It didn’t take me long to get back into the groove,” he says of his comeback. “Although I learnt that my ambition is greater than my ability, I love the sport and there were so many great things to come out of it.”

Higgins says her musical reawakening taught her to deal with self-doubt. “Once I got confidence back, I realised my ability to write songs hadn’t even left me, it was just that I stopped believing in myself.”

Having embarked on her first national tour, she is now revelling in her new sense of purpose. “I’ve been given a certain ability that I love doing and, since getting back on the horse, it all feels fresh and exciting again.”

Missy Higgins performs at Her Majesty’s Theatre, city, on June 17. For tickets, visit ticketek.com.au or call 132 849.