Heard of The Hunger Games? Then you’ll know teen books aren’t just for kids. Luna Soo meets three young adult writers making their mark.

Once upon a time, novels aimed at teenagers were read almost exclusively by teenagers. Now, series such as Harry Potter, Twilight and The Hunger Games have gained a much wider audience with young and old alike devouring the popular novels and pushing them into bestseller lists for weeks, if not months. It seems young adult (YA) novels have finally taken their place in the spotlight – but why? MW talks to three novelists about this recent trend, how their experiences influence their books and why they write for young adults.

Leanne Hall

As a bookseller specialising in children’s literature at Readings Carlton, Leanne Hall has seen a rise in the number of adults buying teenage fiction – for themselves.

“Adults are more open to reading young adult fiction now, but even more should do so,” says the Brunswick resident. “In the literary community there’s a lot of respect for YA novelists, but perhaps less so in the general public. I am constantly campaigning for adults to read YA books. For true readers – people who love words and stories – there’s no reason not to read YA.”

And no reason not to write it. The 34-year-old, who did a graduate diploma in publishing and editing at RMIT, won the 2009 Text Prize for Young Adult and Children’s Writing for her first manuscript, This is Shyness. The prize included a contract with Text Publishing, with whom she published the sequel, Queen of the Night, in February. The books are set in the suburb of Shyness, where the sun doesn’t rise, and follows the surreal adventures of Wildgirl and Wolfboy.

“I knew I wanted to write a fly-by-the-seat-of-your-pants story, but the pieces didn’t really fall into place until I stumbled across the names Wolfboy and Wildgirl while doing research for a short story,” Hall says.

“The idea of a sequel came up with my editor during the editorial process. Then, once the book was out, that idea was encouraged by readers telling me they wanted to find out more.”

Such feedback, she says, is one of the perks. “I love that teenage readers will tell me exactly what they liked or disliked about my books. And I love that I can be raw and gutsy and emotional and out there.”

Hall is not just “out there” in her fiction. She once “crawled across a soccer field on my stomach to see how long it took” in the name of research. Not all her research is so arduous – sometimes simple observations influence her writing, too.

“Queen of the Night features plants in tins and teacups left around Shyness, something I’ve seen around Melbourne in recent years,” she says. Hall also weaves memories of her own adolescence into her books.

“I can remember the emotions of my teenage years vividly. I transpose what I remember about my worries, obsessions, passions and friendships into the modern day and weave them around fictional events.”

The bookseller lists Patrick Ness, Derek Landy and Melbourne’s Cath Crowley as some of her favourite YA writers. “I write because books have brought me so much knowledge and pleasure and escape over the years. I write YA because I read YA.”

Part of the responsibility of writing for a young audience, Hall says, is tackling the big issues – everything from love and loss to intimacy to simply growing up.

“I think the main responsibility for writers is to be empathetic and supportive, and to provide perspective or hope,” she says. “As a teenager, I really appreciated books that voiced how I felt, named the struggles I was having and placed my problems in a larger context.

“I think it’s nonsense to sweep any issue under the carpet. Books are a safe place to try out ideas, mimic experiences, and deliver information.”

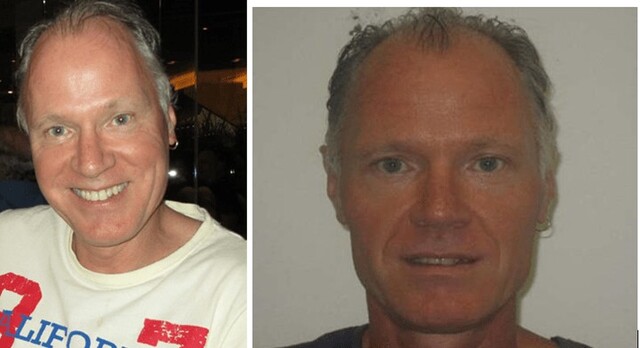

James Phelan

James Phelan, 32, has gone from creating buildings to creating whole worlds. The former architecture student – who worked with Federation Square’s design team while at uni – has written five thrillers for adults (the Lachlan Fox series) and a post-apocalyptic trilogy for young adults.

“Ever since I was a teenager I wanted to be a novelist,” the Richmond author says. “But it wasn’t until I was about 20 and studying architecture that I figured, ‘Why am I going to wait until I retire just to see if I can write a book?’ So I took the plunge; I wrote a book, then I swapped degrees and did English literature [at Swinburne University, Hawthorn] and got a job as a staff writer at The Age. Little did I know what it took to get a book published – I thought writing the book was the hard part! It took me about four years to get my first book published.”

His perseverance paid off. Phelan, who lists Garth Nix and Sonya Hartnett among Australian novelists he admires, has been a full-time author for about five years. He is working on a series of 13 books for young readers commissioned by Scholastic, and a thriller series for adults.

His first book for young adults, Alone, took only 16 days to write, and was published by Hachette in 2010. “I knew the story I wanted to tell, about a 16-year-old figuring out that he could survive on his own and that he had it within him all along,” he says, referring to the book’s main character, Jesse, who must work out how to survive a zombie-like pandemic in New York City with three friends.

“I write quickly anyway – my mantra is that I write fast and edit slow,” he says. “For me, it was really about capturing that essence of what it felt like to be a 16-year-old – not only are you forging your own identity but all your emotions are so raw.”

Zombies aside, Phelan says he draws on his life when writing but also relies on interactions with teenagers to inform and inspire his novels. He spends time with his teenage siblings and does several author talks at schools each month. “It’s very interesting to hear what they’re reading and what they like. It’s a really invaluable insight. I think without that as an author it would be quite easy to forget what it was like to be a teenager.”

He says one reason young adult books are popular with adults is because they offer “clean, accessible prose” and storylines adults can relate to. “We’ve all been teenagers, we can all identify with these stories,” he says. “It’s no surprise Twilight is successful – it’s going to strike chords with older readers because it can take them back to those times when a brush on the arm was a significant thing.”

Regardless of intended readership, he says, the purpose of any novel is to look at life and deal with questions you pose some answers to. “Whether you term something ‘adult’ or ‘young adult’, a book’s a book and you either like the story and the voice or you don’t.”

Pip Harry

Freelance journalist Pip Harry boarded for a term at a Melbourne school when she was 15 – just like Kate, the protagonist in her first novel, I’ll Tell You Mine. The book, published this month by University of Queensland Press, focuses on Kate’s sense of identity as a goth and her difficult relationship with her politician mother. Although the novel is not autobiographical, Harry drew on her past for inspiration. “I went to boarding school because I was quite difficult; I needed my own space. I had a battle of wills with my mum, so I tapped back into that feeling of frustration when I was writing,” the 37-year-old says.

“In all fiction there’s a kernel of truth; thoughts, feelings, people you’ve met, conversations you’ve had – they all turn up in one way or another.”

The co-founder of relationship advice website realitychick.com.au used some of her experiences when writing about Kate’s fledgling romance. Research for other parts of the book involved everything from “rocking out at my desk listening to goth music” to reading work by peers. “I dive into young adult books because otherwise how do you know what’s good?” she says.

Now living in Sydney, Harry names John Green, Kirsty Eagar and Melina Marchetta as some of her favourite teen fiction novelists, and says Australia’s community of young adult authors is “supportive and amazing”.

Finding like-minded writers was a boon for Harry, who enrolled in University of Technology Sydney’s creative writing program at 30. She wrote her first novel when she was 22 but it was never published, which was “kind of devastating”. She worked as a magazine journalist but found she “really missed creating stories and characters”. The UTS course “put that fire back and I still wanted to have a book published”. After a long slog, she has.

“It took me a long time to write the book – three or four years. I wrote slowly, putting it together piece by piece like a patchwork,” she says. By that time, her daughter Sophie was 18 months old and had already changed Harry’s perspective on the mother-daughter issues in the book.

“There’s a scene where the mother and daughter are talking over their differences,” she says. “I rewrote it after having Sophie; I felt more sympathy, more empathy for the mother character. Now I have Sophie I realise she was under a lot of pressure and was doing the best she could.”

Harry says she may one day write for different audiences, but for now she’s sticking to the young adult market. “It’s not a hugely lucrative industry,” she says. “But for me it doesn’t matter, creatively it’s really fulfilling. It’s like breathing in and out. I just can’t imagine not doing it.”