A graceful veteran and a rising star help The Australian Ballet celebrate 50 years of magical dance.

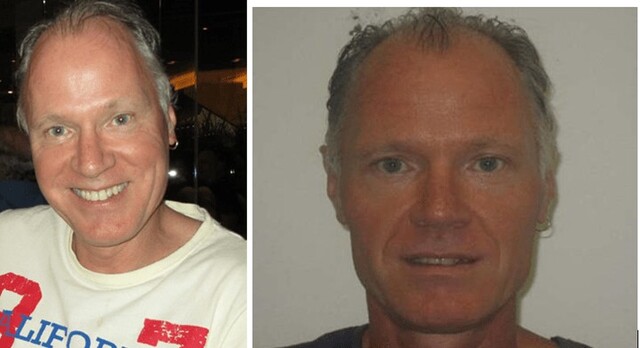

TOES pointed, feet crossed, spine straight as a pole, Joan Boler is the epitome of grace as she sits surrounded by mirrors in one of The Australian Ballet’s training studios. With perfect poise she tilts her head sideways and smiles warmly, just as she would have 50 years ago on the opening night of the company’s first production, Swan Lake, at Her Majesty’s Theatre in Sydney. “It was such an honour,” recalls Boler, who was in the corps de ballet. “We were full of excitement and fear that first night.”

When the applause died down, the dancers swapped their ballet slippers for heels and left through a stage door to sign autographs for the eagerly awaiting crowds. “If I could get up and dance now, I would,” says Boler, with an energy that belies her 70 years.

Half a century later, The Australian Ballet is celebrating its golden anniversary. The milestone spans a performance history of spectacular ballet classics and edgy contemporary work created by Australian and international choreographers.

Before the company was established by J.C. Williamson Theatres Ltd and the Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust, the artform was in a state of flux. Audiences relied on the Borovansky Ballet – then under the artistic direction of Dame Peggy van Praagh – and touring international companies to satiate their hunger for dance.

The Borovansky Ballet disbanded in 1961, and van Praagh became The Australian Ballet’s founding artistic director the next year. She insisted the new company have its own school and offer dancers the security of contracts. It was time ballet was taken seriously. “We were thrilled to be dancing on full-time contracts,” says Boler, who had danced for Borovansky for four years before joining the new company.

The dancers weren’t put off by a gruelling schedule. In the first year alone they toured to every major city in Australia and New Zealand before splitting into two troupes and touring regionally. “We travelled in these dreadful old buses with all the scenery,” Boler says, laughing. At every stop, the dancers would unpack, meet their host families, prepare, perform, bump out and then attend a supper where they were expected to be sociable.

“It was exhausting,” Boler remembers. “There was no emotional support, except for each other. We had no physio, like they do now. We would just cope with it as best we could. There was no way you’d take a day off because somebody might step into your shoes, so you’d just soldier on through injury.”

The show would always go on – sometimes with an extra coat of methylated spirits painted on the dancers’ toes, which were wrapped in an additional layer of lamb’s wool. “Every dancer has danced with blood in their shoes,” Boler says.

Jill Ogai knows the feeling only too well. At 19, she is one of the youngest company members and one of only five dancers accepted into The Australian Ballet this year.

At her graduation performance last year, a bloodied slipper did little to discourage Ogai from chasseing back onstage after a hurried costume change. “It’s the passion and the work that helps push through the pain,” she says. “We’ve worked for hours and hours for one performance. The pain is worth the sacrifice.”

Dressed in her favourite lemon yellow tutu, Ogai is full of optimism and appreciation. She’s been working towards this moment since she can remember. At the age of five, Ogai and her brother huddled on the couch watching a video of Swan Lake performed by the Imperial Russian Ballet Company. Immediately afterwards, the duo told their parents they wanted to start ballet classes. “I really knew it was what I wanted to do,’’ Ogai says.

At 14 she was accepted into The Australian Ballet School and moved to Melbourne from Adelaide. “I was willing to sacrifice living at home with my family to pursue my dream,” she says. “For ballet, that is what’s required – early training.”

Last month, Ogai took her first steps en pointe and on stage as part of the ensemble for Graeme Murphy’s modern take on the classic Romeo and Juliet in Brisbane.

“Suddenly a dream I’ve had for so long is happening,” she says, breathless. “I’m going to work very, very hard to stand tall among such inspiring dancers.”

Not that working hard is a choice. The training regime at the company’s Southbank headquarters can be relentless. The day starts with a one-hour pilates class, followed by a one-hour technical or artistic class and three hours of rehearsals. A 90-minute lunch break is the only interruption before classes take the dancers through to a 6.30pm finish – six days a week.

If a performance is scheduled that evening, dancers will finish at about 3.30pm and are expected at the warm-up bar by 6.30pm.

“The hours are worth it,” Ogai says. “The repertoire isn’t just classic, it’s different. More than anything, it’s exciting.”

Its contemporary take on the classics has helped command a name for The Australian Ballet and secure a new generation of enthusiasts. Graeme Murphy’s striking version of Swan Lake, Stephen Baynes’s Catalyst, and Wayne McGregor’s Dyad 1929 are just some of the performances to have burst onto the world stage.

But it can be difficult appeasing the traditionalists. Boler danced with the company for just over three years, performing in such classics as Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, Giselle and the Nutcracker. ‘‘They were never touched,” she says of the choreography. “I’m very accepting of contemporary ballets but I’m not so accepting of using the old masters and creating contemporary versions. I think the originals are perfect, but maybe I’m just being traditional.”

A lot has changed since Boler’s day. The Australian Ballet initially planted its roots at the Presbyterian Ladies’ College in East Melbourne, and then bounced between there and Fitzroy before basing itself in fibro-roofed Flemington digs for 20 years.

In 1988 the company moved to the purpose-built Southbank space opened by then Prime Minister Bob Hawke. “This venue is made to create dancers,” Boler says with a sweep of her hand. ‘‘And the teachers are wonderful.’’

It’s a far cry from the teaching Boler recalls. ‘‘They were so very strict, we were pummelled and pushed and almost hit in those days,” she says. “We accepted it because that was part of life. You just soldiered on and did your best, did better, because of it.’’

It has been decades since Boler performed before a capacity crowd and danced with tulle brushing against her, but ballet will always be in her life.

She left the company in 1965 after their first international tour, married and had two sons, Scott and Brett. It didn’t take long before she was back in the ballet studio, this time as a teacher.

“I just love it,” Boler says. “I used to go to the park and do grand jetes through the flowers and trees. Once you get the bug, it’s a joy of dance. You have it inside you.”

BALLET BY NUMBERS

IT’S impossible to list every incredible achievement of The Australian Ballet. So here’s a snapshot.

Over 50 years The Australian Ballet has:

• Invested in $40 million worth of costumes and sets

• Sold more than 12 million tickets to its performances

• Danced through 250,000 pairs of pointe shoes

• Performed 7201 shows

• Used 7000 metres of fabric to make more than 700 tutus

• Created Australia’s most expensive tutu, worth more than $5000, for Peter Wright’s The Nutcracker

• Employed more than 550 dancers

• Amassed a repertoire of 389 ballets by 144 choreographers

• Funded 237 commissions

• Toured to 37 countries

• Sparked many a romance, with dozens of dancer marriages

• Produced 12 ballet babies in the past decade

• Been led by seven artistic directors (Peggy van Praagh, Robert Helpmann, Anne Woolliams, Marilyn Jones, Maina Gielgud, Ross Stretton and David McAllister)

The Australian Ballet will celebrate its 50th anniversary with a special Melbourne only season of Let’s Dance: The Australian Ballet and special guests in one huge dance party! starting June 7. Details: visit australianballet.com.au.